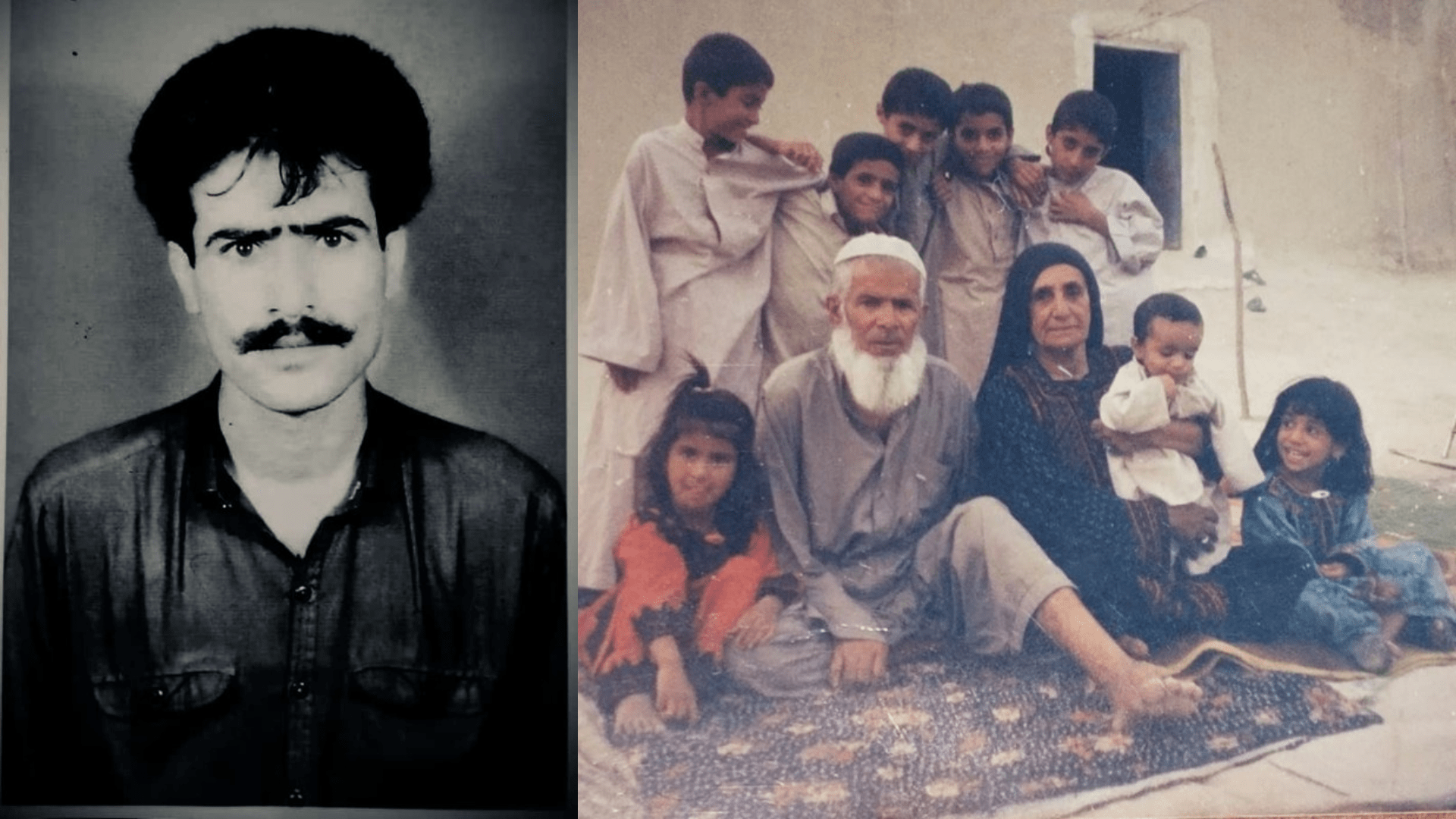

Sattar Baloch was born on December 15, 1968, in the small village of Diz Parom in Panjgur, Balochistan. He was the son of Sufi Dad Mohammed Baloch, and from a young age, he carried a quiet strength and a love for learning that would shape the course of his life. After earning his master’s in Balochi literature from University of Balochistan, Quetta, he chose to become a teacher, not for the pay or prestige, but because he believed in the power of education to lift his people.

Back in those days, education in Parom wasn’t easy to come by. Most kids were sent to the madrasa for Quranic lessons, but for Sattar, that experience was harsh and alienating. His elder brother recalled how Sattar came home from the madrasa shaken, not by the lessons, but by the beatings. He couldn’t see how fear and violence could ever lead to real learning. It didn’t take long for his brother to intervene, asking their father to pull Sattar out and instead send him to an “Engrezi wanag”, an English grammar school. That moment changed everything.

Freed from the confines of that madrasa, Sattar thrived. He fell in love with school, with books, with the idea that knowledge could change lives. He never forgot those early experiences. They became the driving force behind his mission to make sure no child in his community had to endure what he had. He wanted schools to be safe, encouraging places where children felt seen, heard, and valued.

Sattar wasn’t just a teacher. He was a thinker, a man who questioned everything and accepted nothing without understanding it first. He brought this same critical mindset to his everyday life, whether he was teaching or helping a neighbour resolve a land dispute. He stood by the poor, defended the weak, and held firm to his principles even when it cost him.

He began teaching in Kanti Kalag, Parom, and over the years taught in several schools, Middle School Diz Parom, Middle High School Panjgur, Sing-e-Kalat, and Dazi Bunistan. His reach was wide, and his influence even wider. He didn’t just teach subjects, he taught kids to believe in themselves.

At home, Sattar practiced what he preached. To him, education was not just about school, it was a way of life. He kept the children close, away from the growing dangers of addiction and despair that loomed over Panjgur. His home became a place of learning. He would gather the kids in the evenings, give them books, talk to them, and challenge them. He wasn’t a distant patriarch but a friend, a guide, a safe place.

Sattar never imposed. He listened. He gave the children space to speak, to question, to grow. In doing so, he gave them the kind of freedom he had once longed for.

In the early 1990s, Sattar stepped into political activism. He joined Baloch Students Organization with Shaheed Fida Baloch and eventually rose to become president of its Panjgur zone. Later, he joined Baloch National Movement (BNM), where he became a respected voice for the oppressed.

But activism in Balochistan comes with a price.

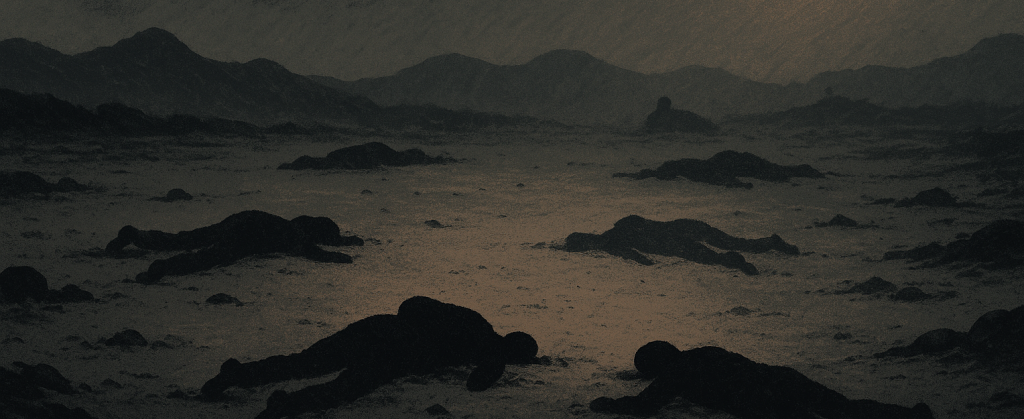

On August 15, 2010, during Ramadan, Sattar was abducted in broad daylight from his medical store. It wasn’t a secret operation, hundreds witnessed it. For nearly nine months, he was held, tortured, and denied every basic right. Then, on May 11, 2011, his body was found in the Peskol River alongside two others, teacher Safeer Baloch and political leader Agha Abid Shah.

His mother, Ganj Khatoon, never recovered. That morning, Sattar had left the house in his white Balochi clothes, smiling as always. He never came back. Ganj Khatoon would often stare at his photo and ask, “Is it possible that my eyes have taken my child so far? He looked so beautiful that day, could my eyes be evil?”

How can a mother not lose her mind when the only things that identify her son are his bones, teeth, and shoes? How difficult was it for her to lay her son’s bones and teeth in the grave instead of a whole body? How can anyone describe these moments for a mother? A child is a mother’s most precious possession, yet what happens when that possession is taken away without any crime? How can a mother not harbour hatred for a state like Pakistan that has taken her son in such a brutal manner?

The people of Panjgoor shut down the town in protest for nearly a month. It wasn’t just a strike, it was an act of collective mourning, of resistance. Sattar, Safeer, and Agha weren’t faceless victims. They were beloved sons of the soil.

Instead, the state answered with bullets. On the third day, an old man named Hussain, known for running a small medical store, was shot and killed. His only crime was standing with his people.

Eyewitnesses recall army vehicles swarming the area. Shots rang out. Soldiers searched frantically for shovels to bury something or someone. Medical reports confirmed what the people already feared, the bodies showed signs of torture. They had been brutalized, erased. But the pain couldn’t be buried so easily.

These accounts may never make it into official reports. But they live on in the memories of those who were there. In Balochistan, where the truth is often silenced, even whispers matter. They tell us that Hussain, Sattar, Safeer, and Agha were not anomalies. They were part of a pattern, a system designed to crush dissent, one body at a time.

Safeer Baloch was a teacher, like Sattar. In a place where many teachers do little more than collect a paycheck, Safeer showed up every day with purpose. He believed in the youth of Panjgur. So did Sattar, who even requested a transfer just to be closer to the students who needed him most. Their murders weren’t just personal losses, they were attacks on the very idea of education as a force for change.

Then there was Agha Abid. A force of nature. His voice carried through the dusty air of Panjgur like a call to arms. Agha’s journey started with student politics, continued with BSO-Azad, and led him to a leadership role in BNM. He studied political science in Quetta, but his real education came from the streets, the rallies, the crackling microphones. He wasn’t just speaking truth, he was living it. And in the end, he paid for it.

Sattar’s story isn’t just his own. It’s the story of Balochistan, of a people constantly punished for daring to dream. For wanting an education. For wanting justice. The year 2011 was brutal. Abductions, killings, disappearances. And through it all, the state kept trying to erase the ones who stood tallest.

But memory is a stubborn thing.

Even as the state continues its campaign, arresting members of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), targeting activists, silencing journalists, but stories remain. Sattar, Safeer, and Agha may be gone, but their voices are louder than ever. Every May 11, their families mourn not just their loss but the loss of hope.

The state tried to bury them. But the Baloch people remember. They speak their names. They keep their stories alive. And one day, when the dust settles and justice knocks, the truth buried in the rivers will rise.