I would never be able to believe that he read all the books he bought. He bought them in dozens. Not once in a month. Almost every week.

“Where can I find Kafka’s collection of short stories in Urdu?”

And he would guide me to a bookshop in Karachi’s Urdu Bazar that the Google Maps would never be able to locate, even in 2050.

“Tell Asif Bhai, Comrade has sent you. He’ll give you 50 per cent discount.”

He loved books. Literature. Philosophy. History. Politics. He loved books on any subject on the earth. I’m not sure though if he loved reading them as well.

“Such people are called bibliomaniac,” Sindhi critic and fiction writer Mumtaz Mahar, my literary mentor, told me as we looked at Sahar Ansari and Comrade Abdul Wahid Baloch buying piles of books at Frere Hall. Every Sunday at the lush lawns of the colonial building, used, new and pirated books were sold at cheap prices.

But the used books scattered over the mud ground of a narrow street of Saddar’s Regal Chowk were even cheaper. I bought most of my books there. If the stall owner didn’t know the literary stature of the author, he would sell you an invaluable book for just five rupees.

“Don’t buy it from here,” Comrade gave me a surprise hug as I was about to buy a book on post-modernism.

“I saw the same book there, in that corner stall. He doesn’t get many customers so you will get it cheaper, and it’s in better condition,” he said.

As a student with little money in my pocket, I would always respect his advice on buying used books at cheap prices. “They (book-sellers at Regal Chowk’s stalls) don’t know which book is worth what. But they are smart people. They judge it from your facial expressions. Never show them you’re dying for this book.”

But the problem was he would buy every nice book before I could find it. Waking up early on Sundays was a torture. But however I tried to reach before him or others at the Regal Chowk book stalls, I failed. He was already there when I reached. He had already bought the books I wanted.

“Do you think they really read all these books?” Mahar, a ferocious reader himself, wondered every once in a while as we saw Comrade or Ansari piling up books at Frere Hall or Regal Chowk. Every Sunday. My answer was in the negative. Even today.

But Comrade was not just in book-buying business. He’s also responsible for most of the Balochi books published during the last three decades.

There is no proper publishing house for Balochi books. A poet would save some money, send his manuscript and the money to Comrade, and he would make sure the book gets published and circulated to major book stalls. He was a one-man publishing house.

Before digital publication got popular in Karachi, a manuscript needed inscription, typesetting, filming etc before the printing process. If the money the author sent for his book’s printing was not enough, Comrade would do some of these works, like typesetting, himself. If he believed in a book, he would pay for all its publication.

“Where does he bring this money from? I’m telling you I don’t trust this guy. Something is fishy about him,” a friend told me once. And this question was asked quite often in Baloch literary circles.

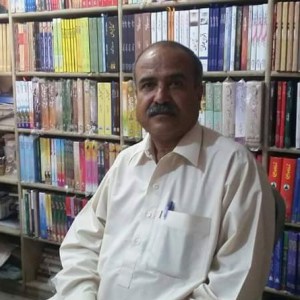

Comrade worked as a telephone operator at the Civil Hospital, Karachi. It was natural people would suspect his source of income when they saw him buying piles of books or printing books for Baloch authors for free.

“They (authors) would say they will send the money. After their book gets printed, they don’t even pick up my calls. And then again one send his manuscript for printing. Where should I take it to? I owe money to almost all the printers in Karachi,” he would go on and on. In a frustrated monologue.

I still wonder why he’s called Comrade. People say he once used to be a hardcore socialist. We never discussed his political background. But apart from our interactions at book shops and stalls of Karachi, I encountered him almost every time I visited the Karachi Press Club. He was there with his kids, wife and a camera. He would take part in the rallies of the families of missing persons, take their photos and help them publish their posters.

“You know what he will do with these photos?” Another suspicious friend – and there was no dearth of them – asked me. “He’s planning to move to Europe and seek asylum with his family. These photos will serve as evidence for his asylum claim,” he decreed with cast-iron certainty.

That friend left Pakistan and took asylum in Europe after the military started kill and dump of Baloch activists in 2009. I also fled although I couldn’t get to Europe, partly due to my laziness.

Those were times when no Baloch man would dare to participate in rallies. Baloch journalists, like me, would not know which word or phrase would get one killed while writing on enforced disappearances and other human rights abuses in Balochistan.

But until recently, we still saw photos of Comrade taking part in rallies for the recovery of missing persons. I grew suspicious too. Why he’s still alive? Why the military doesn’t pick up this man? Why he’s not fleeing Pakistan like most Baloch men who ever said something against abducting people and dumping their bodies by security agencies?

Whenever I saw his photo holding a banner against enforced disappearances, I was reminded of my friend’s words: “Something is fishy about him.”

Finally, he too went missing. On July 26, 2016, he was picked up by masked men from Suhrab Goth when he was travelling from interior Sindh to Karachi.

I wonder who those masked men were. Military folks, most probably, as they do such things more often than others. But they could also be sent by some owner of a printing house to get his money back.

Sajid Hussain (1981-2020) was a writer and senior journalist from Balochistan. He had a degree in Economics, International Relations and English Literature from Karachi University. He had the experience of working with Pakistani newspapers Daily Times and The News International. Sajid Hussain was also the founding editor of this online magazine.