A R Daad short story Hasan Sòl is a modern parable. Fazal Baloch has translated it from Balochi.

Even after much medication and treatment, the lamp of his fate refused to glow. His wife had also tried everything she had been told could be helpful.

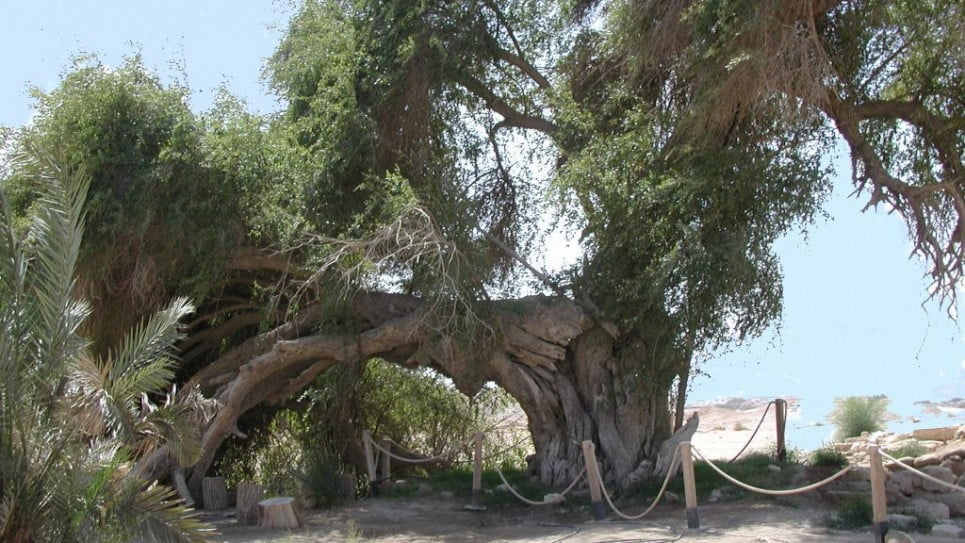

One day, a colleague at the office told him there was a jujube tree in the mountains facing the town and he would be blessed with a child if he spent a day and a night under its shade. He was desperate. He had wasted himself because of the sorrow of being childless for the last five years.

That morning, he wrote a leave application, placed it at his boss’ table and left.

After a tedious journey, he finally reached under the jujube tree. He felt like as if the doors of heaven had been opened on him. For a while, he couldn’t recall why he had come there, as his body had almost collapsed after the day-long journey.

As he reclined against the tree, he drifted off to sleep. When he opened his eyes, the silent night and the dark of the jungle had unleashed a snake into his soul. Once again he reflected that why had he come here? He seemed to have forgotten everything; the language he spoke, the location of his hometown. He stood up silently under the tree and cast a glance around.

“I think I have seen this old man somewhere before. But now I cannot recall when and where it was? Perhaps I have seen him in a dream”.

He contemplated over it and then caressed the jujube leaves. He felt hungry. He had already consumed whatever provisions he had brought for the journey. His mouth watered with the sight of the ripe jujubes. When he stretched his hand to pluck off a few, a voice startled him:

“What do you seek standing here in this darkness”?

“Sir, I am an unlucky man. I have no child. People from my clan joke that I am sterile. I have been to everywhere. I have knocked all doors but to no avail. I came here with empty hands so that you fill them with your blessings.”

The jujube tree replied:

“Promise me, the Hasan Sòl, that if it happens to be a girl, she is my fiancé and her name will be Nòk Madìna. And if it turns out to be a boy, do what you and your wife like.”

“Sir. I accept happily whatever you bestow upon me. I wouldn’t back down from my promise. I belong to a clan whose people always honour their words.”

The sun had risen now. Amid the chirping birds of jungle, Hasan Sòl had fallen silent. He looked around, relaxed and contended.

Back at office, now he sang in a loud voice, and after finishing paperwork his fingers unknowingly banged the table as if it was a drum. His co-workers sitting close to him looked curiously. The colleague who told him about the jujube tree was smiling.

He was no longer the man who would not talk to anyone from the time he entered the office in the morning till he left in the afternoon. His colleagues had always wanted him to talk to them, to have a cup of tea with them and discuss their salaries and the current issues of the city. But unconcerned with all of them, neither had he talked to anyone nor greeted them while he entered the office.

It had been a year since his colleagues were worried about his loud singing and table beating. But indifferent to all of it, he was so elated over the birth of Nòk Madìna that to him pain, sorrow, hopelessness and the sufferings people would whined about were meaningless. He felt nothing but happiness. In those days he began hanging around at new hotels and restaurants of the city. He visited newly-constructed buildings and roads as if he was a newcomer in the city. For him everything was new. He made terms with some old drunkard friends.

Every Sunday, he went for picnic with those friends, and they drank. After two or three glasses, his friends began whining about society but he seemed unmoved because he had consumed such a drink that enables a man to forget everything, for a while. At such moments he would stand up and gaze the trees and mountains around. He never liked his friends complaining about other people.

On Monday morning, as usual, he got up, took a shower and left for the office.

He now liked the honking vehicles and school-going kids carrying bags on their shoulders. Everything appeared meaningful to him. He had grown so used to high-pitch singing and table-beating once he finished his office work that it seemed to be part of his job description.

,

After sixteen years, he was sad again. One morning when he was about to leave for office, Nòk Madìna, also ready for school, asked him:

“Dad! I dreamt of a jujube tree last night. As if it wanted to say something to me.”

He smiled and replied: “It’s a dream, child. You can see anything in a dream. They don’t have any meaning. Pay attention to your studies and don’t give any thought to the dreams.”

He hurried towards office. Everything looked exactly like what they did 16 years back. Every word of school-going kids, honks and horns of vehicles all reminded him of the promise he had made with Hasan Sòl. He ran his hand around his face. It felt like the face he wore sixteen years back: a bony face without any layer of flesh. When he entered the office, a colleague held his hand to greet him but he couldn’t utter a word as if he didn’t know the ritual of greeting. He moved forward and sank in his chair as if someone forcefully threw him into a well.

“The jujube tee, Hasan Sòl, Nòk Madìna and dream…” He reflected and cupped his head with both hands.

All colleagues sitting close to him wondered what had happened to him. Neither he his pen was moving fast enough nor his paperwork was efficient. Neither he sang loudly nor banged the table. As if he had never done any such thing. As if someone else had been occupying his chair and the man had come back after sixteen years. He did not know his office work nor he did he know of the art of high-pitch singing and table-beating.

He again reflected: “The jujube tree, Hasan Sòl, Nòk Madìna and the dream. What does that mean?”

He stood up and stepped out of the office. For a moment he thought to go to Nòk Madìna’s school to meet her teacher and tell her to ask her student not to see the jujube tree in her dreams again, otherwise he wouldn’t live. A car from far behind honked. He moved aside and changed his direction. He spent the whole day brooding over and over about Nòk Madìna’s dream and went home after midnight. His wife was still awake. He said nothing to her and laid down on his bed. Again the same thought appeared in his head: the jujube tree, Hasan Sòl, Nòk Madìna and the dream.

After quite some time, he finally drifted into sleep.

As soon as he opened his eyes, he thought of calling Nòk Madìna and ask her, “Did you see that dream again?”

Nòk Madìna came herself.

“Daddy! I saw the dream again and now I feel like the tree was a man who was calling me out.”

“No. Not at all. He is not a man, child.” It is a mere dream and dreams don’t carry any significance.”

He didn’t know what he said and stood up and made it to the bathroom.

On that morning, Nòk Madìna along with her friends went for a picnic. After the lunch they climbed up a mound to pick up jujubes. Laughing and crackling they stopped near a giant old jujube tree.

Nòk Madìna thoroughly looked at the tree. She felt that it was the very tree that appeared in her dreams every night.

“No, no it is not that one. All jujube trees look alike.”

After having filled their pocket and cups of their palms, one by one they climbed down the mound. Nòk Madina’s scarf entangled with a branch of the tree. As she turned to free her scarf, she felt someone had held her hand. She blurted out:

“Waiy! What a damn jujube”.

A voice reached her ears:

“Listen.” Nòk Madìna looked around, but nobody was there. She found out that all her friends had descended down. “I am the jujube tree talking to you. When you go home, ask your father to honour his promise. If you forget, you will find a box at the head of your bed. Open the box, a wasp would come out and sting one of your fingers and reminds you of my words.”

She freed the hem of her scarf and quickly climbed down as if being chased by a beast. She was soaking in sweat. Her lips were trembling. She wished to go home as soon as possible. Their vehicles was ready and all were waiting for Nòk Madìna who had been left behind. They reached home at dusk. She collapsed as if she had not slept for years. As she opened her eyes in the morning, she found her father standing in front of her carrying the box.

“I think you brought this one.” Astonished, Nòk Madìna tried to recall that if she had brought it or it was there before but she couldn’t remember anything.

“I don’t know if I have brought it or it was here before”.

Both father and daughter sat in front of the box. It was a beautiful box with carved patterns on all sides. When they opened the box they only found an old book inside. Its pages had turned pale. He turned the first page and read:

“It is the reward of my good deeds that I have been transformed into a jujube tree but you haven’t honoured your promise yet”.

As she read the word jujube, Nòk Madìna remembered the other day’s picnic and the words of the jujube tree. She wanted to share them with her father, whatever the jujube tree had told her but by then he had reached at the door and she didn’t want to call him back.

Nòk Madìna wished to ask her mother: “What is the mystery between my father and the jujube tree?” Her mother coughed such a cough as if she felt a slump in her throat and before Nòk Madinà could ask her, she came up with the false reply: “I don’t know my daughter” and strolled towards the kitchen.

Nòk Madìna was now the source of his worst agony.

“Daddy what does the jujube tree want?”

He never wanted to tell the truth and deprive himself of his daughter but concealing the reality was worse. Now most of the time he would wander outside and return home late in the night and before Nòk Madina opened her eyes he would leave for the office. Leaving office early, wandering across unknown roads and spheres of the city and returning home late in the night had become his routine. He disliked all the trees in the town.

Wandering, when he came across a tree, he would spit at it and if he saw a traveller sitting under a tree, he would look him with contempt.

“If Hasan Sòl happens to come across me on these roads I will chop his head off,” he thought to himself and kicked an empty cardboard box lying before his feet. People passing by looked him in such a way as if he was out of his senses.

On that night he splurged all his money on wine. Tumbling, he returned home and shuddered Nòk Madìna out of her sleep and told her: “Everyday you ask me why the jujube tree appears in your dream or what my relationship with the jujube tree is. Then listen. You are fiancé of that tree; you are fiancé of Hasan Sòl, the old man who sent the box to our home. Come, I will escort you to the land of your fiancé. I can’t bear this curse anymore.”

His tumultuous voice woke her wife. He held her daughter’s hand was about to leave when her wife crossed her path.

“Kill me first and then take her away,” she said.

“Today I am not going to listen to anything. What else you call death? When had we been alive that you fear dying today?” He pushed his wife away and left.

Nòk Madìna was confused. She didn’t know what had happened. The night was deep and dark. The fountain of love in his heart had drained out. He didn’t wish anything for her daughter anymore. He was only thinking if he would live tomorrow, go to office, sit with his colleagues, discuss the rising issues of the city, bang the table and sing songs in a high-pitched voice. Thinking and brooding, he reached there at dusk. He called out loudly:

“Hasan Sòl, here is your fiancé. I have honoured my promise.”

He left Nòk Madìna’s hand and descended down. As if he had relieved himself of a huge burden. He felt so light and easy that covering a long distance for him was a child’s play. As if he was kicking a football down home. The sun had risen. Kids carrying their school bags were on their way to school. The entire city was awake. Everyone was heading somewhere. Without looking at anyone, he went right into a saloon, took a shower, made a shave and left for office, whistling.

Fazal Baloch teaches Urdu at Atta Shad Degree College, Turbat. He is the first regular translator of Balochi literature into English.