“Do you want to become a Sabzal Samagi?” my father shouted before attempting to burn my poetry books. I understood his frustration as he wanted me to focus on my textbooks, but why on the earth he thought I wanted to become Samagi, who had nothing to do with poetry.

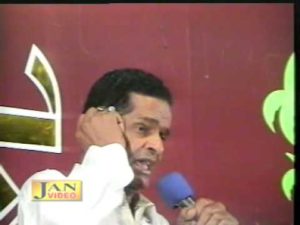

Samagi is a Balochi singer, long out of business. When my father was young, Samagi was the most popular singer, at least in Makran. With his dark complexion and African hair, he was chased by girls like a rockstar. Despite belonging to the lowest class in the Baloch tribal system, he married a girl from a royal tribe.

A wedding ceremony without a performance by him attracted little guests. His performances were unique. He was accompanied by transgender dancers. They danced and flirted with the guests as Samagi sang.

When my father was young, almost thirty years back, he traveled five miles on a dirt road on a borrowed motorbike to attend a wedding ceremony. He was not invited. You didn’t need an invitation to a wedding where Samagi was performing with his dancers, who were dressed like women.

“Rupa, Asia, shake it baby,” Samagi would shout on mic whenever his dancers would slow down and sleepiness overwhelmed guests as dawn neared. On Samagi’s instigation, the weary dancers would resume following his upbeat wedding songs.

My father returned home a little before dawn that night, taking every step with care so as not to wake up his self-taught mullah father. But he was awake. Even he knew there was a Samagi performance five miles away and that his son is not going to miss it. He pretended he was sleeping, a clay brick in his hand, waiting for his son to reach within his throwing range. When my father was in the range, the brick hit him at his leg. He limped for weeks.

Samagi also limps these days due to some illness, but he cannot afford treatment. It has been years since he was invited to a ceremony. God knows where his famous transgender dancers have gone. There is no place for them in today’s Balochistan.

The mushroom growth of madrassah-taught mullahs, who have spent years at radical seminaries in Karachi and Punjab, has changed things. Even my self-taught mullah grandfather is upset with them.

“Every once in a while, someone will come with a lot of money in his pockets wanting to renovate my mosque. I want it as it is,” he says.

This money comes from Sindh and Punjab’s large seminaries. Also, hundreds of thousands of Baloch living in the Gulf countries, especially those working with religious sheikhs, help bring money to build mosques even at places where no one lives nearby. Bahrain is a center for funds collection from Saudi Arabia to turn Iran-neighbouring Balochistan into a Salafi stronghold.

Balochistan has been relatively a secular and liberal society, if compared with neighbouring cultures. Women had not been killed for honour. Nor had they been forced to cover their faces. Tribal code, not religion, governed society.

Singing had been an essential part of every important occasion. On the birth of a child. On the circumcision of the child. On marriages. On death. On parting away of a loved one. While catching fish. While grazing animals. While riding a camel. Each genre has a name.

Most singers had been women. Sharuk Irani, Mahrang, Haan Bibi, Guluk, Sharifa Sauti (Sharifa the singer), Ganjan, Duri. Now singing comes only under men’s domain. Occasionally, for a duet song, a non-Baloch women singer is hired whose Balochi pronunciation tickles your ears.

“When I’m writing a film script, I’ve to keep in mind there shouldn’t be a scene where a woman has to be there. The women have to cut out their face if they want to share a photo on Facebook. Appearing in a movie is another thing,” filmmaker Dr Hanif Sharif once told me.

He’s a meticulous filmmaker. He drafts his scripts where women are not needed. But others don’t mind being laughed at. In their movies, they make a man dress like woman and usually the camera can only see his back. Sometimes, a husband calls his wife (who is not shown on the screen) for a cup of tea. “One minute,” says a voice, which emanates from a man’s throat but squeezed so as to sound like a woman’s.

In 2013, a filmmaker, Rashid Hasan, dared to star an Iranian woman in his movie Bemurad. On the social media, even the ones who have a liking for the words “liberal” and “secular”, criticized him for corrupting the Baloch culture. The Baloch Students’ Organization (BSO) stood up for him, but the group is too weak these days to make an impact.

Created in 1967 on leftist values, the BSO has played a key role in countering the radical Islam, apart from keeping the separatist sentiments alive among the Baloch. It’s said every Baloch has once been a member of the organization if he ever attended school, college or university.

Once my grandfather was asked to exorcise a newly-married young woman. He usually suggest such people to see a psychiatrist. But they were stubborn, so he went with them to take the jinn out of the young woman.

“Whether you’re a jinn or a fairy, leave this woman’s body at once,” he ordered in typical Balochi exorcising expression.

“Mullah! Don’t you dare to mess with me. I’m BSO’s president and I love this woman,” the woman replied in a possessed voice.

My grandfather came to the conclusion that the young woman had been married against her will and that she loved some BSO guy.

The BSO had such power that its separatist slogans used to be chanted as songs at weddings. But the government of Pakistan has banned it now. Its members are being hunted and killed since the military has initiated a notorious kill-and-dump operation against Baloch nationalists to crush a separatist insurgency. At schools, colleges and universities, the group has long been unable to arrange study circles where Marxist and nationalist literature is taught.

When an earthquake happens in Balochistan, Jamaat-u-Dawa (JuD), the charity wing of the international terror group Lashkar-e-Tayaba, or other religious groups are brought under military protocol to help the victims and at the same time raise the “long live Pakistan” slogan.

Earlier this month, the JuD claimed if Pakistan’s flag was still being seen in Balochistan it was only because of their efforts. And Pakistan’s military establishment — which has often relied on Islamists as their strategic assets against Afghanistan, India and Balochistan – understands that Islam is the only link that can keep Balochistan bonded with the rest of the Pakistan.

But it’s unfair to blame the military establishment for the lack of a female Baloch singer or actress. The blame goes to reactionary Baloch nationalism and the degrading roles women actress get in Punjabi films, in part, at least.

“Should we let our woman to be dishonored like they’re being in Punjabi films,” a young Baloch nationalist told me once when I had asked him why they were against women to sing and act.

As the women are disappearing from the Baloch cultural scene, they are rising on the political front. The military hasn’t yet started killing nationalist women. As the Baloch men are on the run, women are getting ready to replace them. For the first time in BSO’s history, its chairperson is a young woman, Kareema Baloch.

That young woman my grandfather tried to exorcise was supposedly possessed by a jinn. If next time he is invited to exorcise a young man, it might be a fairy.

Sajid Hussain (1981-2020) was a writer and senior journalist from Balochistan. He had a degree in Economics, International Relations and English Literature from Karachi University. He had the experience of working with Pakistani newspapers Daily Times and The News International. Sajid Hussain was also the founding editor of this online magazine.

An extremely powerful piece. Thanks Waja Sajid for putting all these important cultural and political challenges, taboos and opportunities in one single piece. Loved reading every word of it.

People around the world are planing to make a living in outer Planets and here we are limited to a few career choices only cause ”we born saint” .

and apparently, people are so good at screenshot-ing pictures, cutting head out and labeling them as their own that they will not even bother to take pictures of their own.

Just hoping for the day when our tribe will start thinking out of the box.