Last week, the narrow streets of Passini — a coastal town nestled beside the Arabian Sea in Pakistan’s Gwadar district — overflowed with people. Men walked with clenched fists. Women’s voices cracked as they chanted “Kamsin Sahil Kay Qatilon Ko Giraftar kar kay Phansi do.” Children, some barely older than the boy they were marching for, joined the crowd — not fully understanding, but old enough to scream.

What filled the air wasn’t the usual scent of salt or fish or diesel, but grief. Grief, and fury.

This was not a protest. It was a procession of the broken.

They carried placards scrawled in trembling hands: Justice for Sahil.

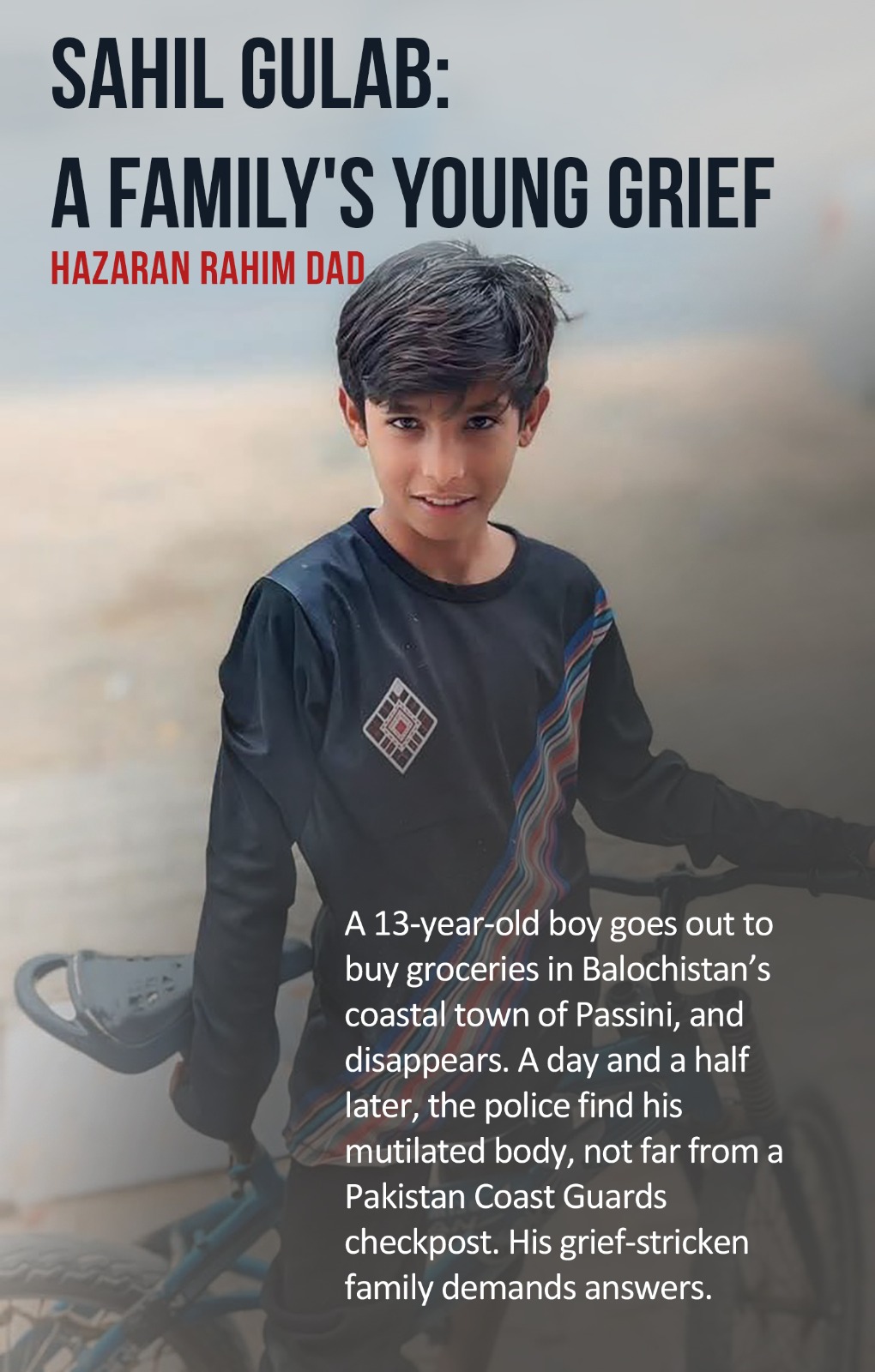

Sahil was 13 years old.

The son of Gulab, a fisherman — one of many who spend their lives reading tides and mending nets. But Gulab could never have imagined that the greatest danger to his son would come not from the sea, but from something lurking on dry land.

On the night of April 4, Sahil left home around 8 PM. His mother had asked him to fetch ghee and sugar from the nearby shop — a small, ordinary errand in a town where nothing ever seems to change.

But Sahil did not return that night.

Not the next day either.

And on April 6, the town found him — dumped and mutilated. A child silenced forever.

The protest was led by Sahil’s elder brother, Ahmed. A young CA student, he was forced into a man’s grief overnight. He held the mic like it was a lifeline — or a weapon. His voice didn’t shake. It thundered.

“If my brother’s killers are not arrested within a week,” he said, surrounded by hundreds, “I will lead a sit-in at Zero Point.”

Zero Point — the arterial lifeline of Passini, where buses snake their way from Turbat, Gwadar, and other areas to Karachi. Where fish trucks crawl at dawn. Where all that is living, or leaving, must pass.

Small girls held posters that read, “Nahil Intezamia Murdabad.” A young boy clutched a placard that said, “Sahil ke khandan ko insaf do.”

And then came Sahil’s mother — dressed in a burka, only her eyes visible. In those eyes, layers of tears had gathered, refusing to fall. Her hands trembled as she held a small photo of her son, Sahil. On it, a single line was written:

“Sahil Gulab ke qaatilon ko giraftar karke saza do.” According to his family, Sahil first went to a nearby shop. When he found it was out of stock, he headed toward another store in the main bazaar. Several locals later recalled seeing him walking in that direction. The power was out at the time — as it often is — and a car was seen passing through. But Sahil never made it to the shop. He disappeared.

It was April 4, around 9:45 PM.

Ali Ahmed, Sahil’s elder brother, was outside with a friend when he briefly stepped into the house — and noticed something odd. One of his younger brothers stood at the gate, eyes anxious, movements hurried.

“What happened? Why are you in such a rush?” Ahmed asked.

“I’m looking for Sahil,” the boy replied, already turning away into the night.

A chill ran through Ahmed.

He walked inside and found his mother, sitting in worry. Her voice cracked before the sentence could finish.

“I sent Sahil out to get sugar and ghee. I gave him 500 rupees. He hasn’t come back.”

That had been hours ago.

Ahmed didn’t wait. He shot out of the house and into the streets, heart pounding like footsteps on gravel. He searched every alley, every turn in the bazaar, every corner Sahil might have wandered. He knocked on relatives’ doors. Called every number he knew. Walked until the soles of his feet ached.

By 3 AM, the town had curled into sleep.

But Ahmed had found nothing.

Only the silence of a brother who did not return.

Two of their relatives were in the police. That night, the family called them. They assured them that the Gashti team — the patrol unit — would begin searching.

The next morning, Ahmed and his uncle Anwar walked to the local police station and filed a Talash-e-Gumshudgi — a missing person’s report. A formal request wrapped in helplessness.

Then they turned to the only place left: the digital world.

A photo of Sahil began circulating on WhatsApp and Facebook — his face frozen in innocence. Above the image, in bold Urdu script, were the words: Talash-e-Gumshudgi.

The police told the family they were searching too. They said they had checked all the known places — but Sahil was nowhere to be found.

But Ahmed could not sit still.

He gathered his cousins. They fanned out across Passini like scattered prayer beads — asking, knocking, pleading. From Sahil’s friends’ homes to strangers’ doorways, they asked the same unbearable question:

“Have you seen this boy?”

No one had.

April 6, around 10 AM. Two days after Sahil vanished, his family stood outside the Passini Press Club — placards in hand, prayers in their throats. The morning sun bore down, but no one moved. They were not just demanding answers. They were asking to be heard.

Ahmed approached the police again.

“Any update?” he asked, voice hoarse, eyes red.

The answer was the same. “Nothing yet.”

But then came a call — sudden, cold, final.

It was the police. They told his uncle to come near Shah Jan Hotel. No explanation, no details. Just: Come.

They rushed there. The scene was thick with uniforms — DSP Zahid, Levies officers, and a sea of bystanders. Ahmed pushed through the crowd.

And then he saw it.

A patch of bushes.

A body.

Same white clothes.

It was Sahil.

He was lying in silence. His small frame looked even smaller now. His uncle collapsed into tears, the kind that breaks open like earthquakes. His cries tore through the street.

They carried Sahil’s body in the back of a police pickup — the daala of the DSP’s vehicle. Ahmed took off his chadar and draped it over the little boy, shielding what was left of his brother from the world.

“I couldn’t look at his face a second time,” he said. “It was so tortured, so unrecognizable…”

He turned to DSP Zahid, his voice shaking.

“How can someone do this to a child??”

There was no answer. Only the weight of silence.

Ahmed and his uncle followed the body to the RHC hospital Passini.

He stepped aside, made a call. “Tell Amma to call off the sit-in,” he said to a friend. “Just say there’s some development.”

“My mother has blood pressure,” he said. “I didn’t want her to collapse in the street.”

He left his uncle with Sahil’s body and rushed home — the kind of ride where you don’t feel the road under your tires, only the storm inside your chest.

But when he arrived, she wasn’t there.

“She had gone to the Mullah,” someone said. “To ask for a prayer. For Sahil’s safe return.”

Ahmed got back on his bike. Found her. Brought her home.

She was trembling. The kind of trembling that comes when your body knows something before your mind is willing to believe it.

By then, people had already begun to pour into the house.

Ahmed looked at her — his mother, who had raised him and Sahil both — and couldn’t do it.

He lied.

“No, Amma. Maybe it’s someone else’s body. We’re still looking for Sahil.”

He watched as her face held onto that fragile thread of hope, as if belief could bring her son back.

A First Information Report was finally lodged — a promise, on paper, to find Sahil’s murderer. But paperwork didn’t matter now. Sahil had already returned — in the most violent way a child can.

By the time he was brought back, over 40 hours had passed.

His body had lost its shape.

“I was trying to clear the sand from his body,” Ahmed recalls. “And the skin… the skin started peeling off.”

‘There is no language to explain that moment. Just the image of a brother, wiping the dirt off another brother’s lifeless body’.

According to Dr. Mohammad Jan, Medical Officer at RHC Passini, who initially examined the child’s body, it appeared to be around two days old and was mutilated. “It seemed the murderers had choked his face and neck,” he said. “The face was unrecognizable.”

No marks from sharp objects or bullets were found on the body. “The body was giving off a strong smell and had begun to lose its shape,” he said. “If it had been lying near any house in Passini, people would have noticed. It was likely kept outside the town and then dumped.”

He noted that the body wasn’t swollen, which suggested it may have been kept in an open, ventilated space — like a veranda — for two days before being found.

Little Sahil was buried without a ghussal.

The earth received him as he was — sand still clinging to his body, no final wash.

Because martyrs, they said, are not to be washed.

When they finally told his mother — not the full truth, but the truth as gently as tragedy would allow — they said:

“You are now the mother of a martyr.”

She didn’t faint. She didn’t scream.

She stood still, like a woman holding back a flood.

“They told me I was the mother of a martyr,” she says, her voice flat, distant, as if speaking across a great canyon of pain. “And from that moment, I held back my tears.”

“I told myself: I will not cry now. I will cry when Sahil’s murderers are found and punished.”

“That day, I will cry. I will cry a lot.”

She does not say this dramatically. She says it like a promise.

Sahil was not just a child — he was that child. A class-topper. The first to arrive at school, the last to leave the blackboard. After Sahil’s murder, a small video began to circulate. In it, Sahil is alive. His voice rises: “People say Ronaldo is king,” he argues, “but there’s only one king — and it’s Messi.” He smiles.

His brother, Ali Ahmed, remembered it too. “He loved Messi,” he said. “Left-footed. Quiet. Dangerous. That’s how Sahil saw him — and he wanted to be like that.”

A boy who debated football is now debated in whispers, in a police file, in press clubs.

What meaning do football dreams carry when a boy with 500 rupees in his hand does not return. He had just passed his 9th grade at Government Higher Secondary School Passini. Now, his notebooks are still at home. Unfinished. Untouched.

Sahil’s body was found just half a kilometer from the Passini Police Station — barely a two-minute walk from the Coast Guard checkpoint. It had been dumped on the edge of the main road, near a cluster of trees.

According to the police, a Levies officer discovered the body and informed them. Passini Police SHO Shakeeb Arsalan stated that the police had raided several areas in the search for Sahil, and “perhaps that pressure forced the murderers to dump the body.”

At the scene, Sahil’s slippers were missing. But the 500-rupee note his mother had given him to buy groceries was still in his possession.

Since the child didn’t have a mobile phone, police say it’s been difficult to trace his last known location. However, SHO Arsalan claimed, “We will soon find out the murderers. They cannot stay hidden from the law for long.”

A little boy who carried Rs. 500 to buy sugar and a bit of ghee is now carried only in memory — too light for the grave, too heavy for the heart. A boy still small enough to forget which pocket he’d put the money in.

He walked into the night, like thousands of children do in every poor street of a forgotten town. But the power was out. A car passed by. And Sahil vanished into the darkness — forever.

The day his family and others protested for his return was the same day his body was thrown away like trash. When the news came, people gently sent his mother home. But home held no comfort. She wandered instead to a mullah, looking not for answers — just for breath.

At the protest site, the other women stayed behind.

A journalist at the Passini Press Club, who had come to cover the demonstration, later said, “I cannot express this unimaginable scene in words. I was there when they were chanting slogans — and watched how those slogans turned into wails and sobs. It cannot be described.”

The killers remain unnamed. The administration says the investigation is ongoing. But the Baloch Yakjehti Committee points to what many here already whisper: the shadowy presence of local, state-backed militias — actors known to patrol these small towns, to control them.

What does protection mean in Balochistan? This is a province where every kilometre is flanked by a checkpoint. Where armored vehicles crawl through every street. Where security forces are omnipresent — except when a child is abducted, mutilated, and discarded like refuse.

Who killed Sahil? Will justice come? The questions echo. But perhaps the more urgent one is this: Who has the right to live safely in this country — and who does not?

In the end, all that remains is the 500-rupee note his mother gave him — still folded in his pocket when they found his body.

It is the only witness now.

It cannot speak.

His family, torn open by grief, has given the state one week.

One week to find his killers.

One week to name the darkness that did this.

For now, they say, the administration is cooperating. For now. But culprits have not been traced yet.

And somewhere, between protest slogans and prayer beads, between police reports and school registers, Sahil’s mother waits.

Not just to mourn.

But to cry — for justice.

And in this entire ordeal, Gulab — a fisherman who spent his life battling tides and returning home with the salt of the sea in his veins — has fallen silent. The man who once ran his household with the strength of his back now sits with his head bowed. Grief has stolen his tongue. Tears are the only language he speaks.

Hazaran Rahim Dad is an MPhil scholar in English Literature and a feature-story writer. Her work primarily explores the experiences of Baloch people in war, violence, and socio-political struggles in Pakistan.