Sajid is not missing anymore but he was wrong when he said the missing haunted more than the dead. He proved those famous words of his wrong with his death, which is haunting me significantly more than his disappearance. I wish he was still missing.

It’s painful to write about a friend after he dies in such mysterious circumstances. My hands are shaking and the heart is heavier than before. It hurts to process this ugly truth. I want to live in denial. I still want to hold on to the false hope that he will return.

When Sajid disappeared, a mutual friend asked me several times to write something about him. I wanted to but couldn’t find the strength. This made me feel guilty but I feared that I would not be able to do justice to him or his memories. Deep down, I was afraid he might not like it and did not want to make myself or him feel embarrassed upon his return.

To be honest, I have not even read the pieces written for Sajid or listened to the podcasts. I did not have the heart. I have lost quite a few people in my life and the agony of each new loss opens old wounds. The stories of longing cause me unbearable pain. However, it is different today. Today, I want to ease some of that pain by reminiscing on the memories of an old friend who disappeared one day and never came back.

I first met Sajid in the mid-2000s. I had enrolled in an English Literature course at the University of Karachi, and so had he. I noticed him on the first day, not because he was a few years older or looked nerdy with a bag and a few books in his hands, but because he was the only male in the class of around 50 students.

We had an Indian teacher for the first part of the semester who taught us Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. She was particularly fond of Sajid because of his understanding of the classic literature. It was my first experience of critically analysing a novel, so mostly I was in awe in the class and a silent listener. But Sajid looked like he had been critically reviewing novels for years. Although he sat at the back in one corner of the class, he was very active and deeply involved in the class. He would ask questions, make notes, participate in all the discussions and would leave us all pondering about the lesson.

One day, I can vividly remember, we were analysing feminist approaches to literature and he suddenly said something that moved me as a young girl living in a male-dominated society. He said that science had confirmed there was no difference between the brains of a man and a woman, and hence a man was not intellectually superior to a woman. It may sound like an obvious fact but it was the first time I was hearing a man, let alone a Baloch man, accept that women were intellectually equal to men and that thinking otherwise would be scientifically wrong. Afterwards, I often found myself repeating Sajid’s words whenever I got into a gender-related debate.

His major was Economics but he was more fit for literature. The English Literature class allowed him to be himself. He seemed more interested in the English prose than poetry. Excuse my bad sense of humour but I think that was because he knew even then that there was a writer inside him and not a poet. Once, I also saw him show a story he had written to our teacher and receive accolades. It was a great learning experience and I owe it to Sajid as much as I owe it to my teachers. Had it not been Sajid’s curiosity, questions and arguments in the class, I wouldn’t have learnt much.

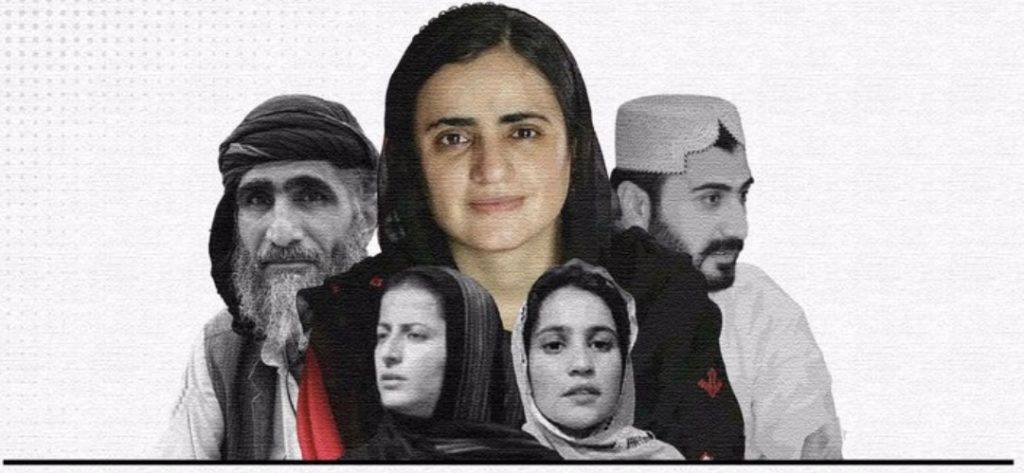

When we were done with the course after two years, we went on with our respective lives and did not cross paths until we met virtually on Twitter. He was now a married man with a daughter and was also a renowned journalist. He was brutally honest in his writings and was a unique storyteller. I would read his columns and stories with immense pleasure.

He then had to leave Pakistan because his pen had put his life in danger. We would talk to each other from time to time. Once, I cannot recall if he was in Oman or Africa, he told me about the frustration of life in exile. He said he was living in isolation at a farmhouse where the only thing that he had access to were books that he would read for hours and hours.

Last year, I penned down my experience of growing up in Karachi as a Baloch girl. I asked the mutual friend to send it to Sajid as I did not have the courage to do it myself, fearing it would not meet the high standard Sajid demanded. In my heart, I was quite certain he would reject it after a single glance. But when he published it on the Balochistan Times website, it helped build my confidence in my writing skills. When he appreciated my second column, it was again a huge confidence booster for a struggling writer like me.

He contacted me a few months before his disappearance and asked to assist him in managing the Balochistan Times as he was going to get busy with his Master’s degree at Uppsala University. I accepted the offer and even a day before his disappearance we exchanged WhatsApp messages. We were supposed to have a Zoom-meeting with the other staffers of the Balochistan Times. I excused myself as I was a bit under the weather and the meeting happened without me. I had no idea what the next day would have in store for us. I heavily regret now for not participating in that meeting.

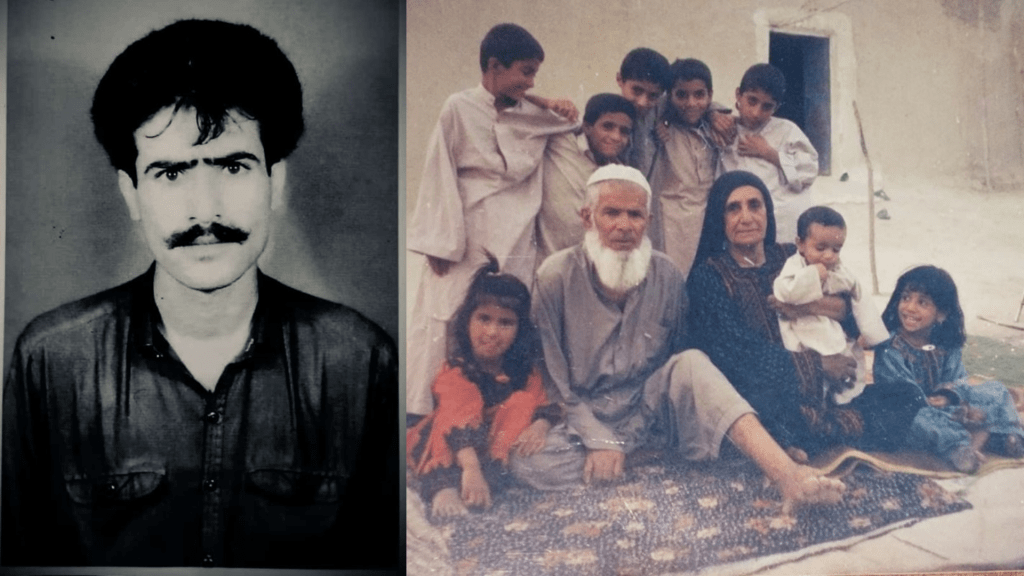

My thoughts go out to his wife, children and parents. The rest of us will mourn his death and then, as it always happens, we will move on. Yes, we may remember him once every year on his death anniversary and that’s it. But, it’s an unending anguish for his family and no one can replace him.

I speak from personal experience. I have felt closely the silent suffering of my family members when my uncles were martyred. I have seen my great-uncle’s white beard turn yellow from the inexplicable pain of losing his last remaining son in Karachi. My paternal aunts became widows at a very young age, many of my cousins grew up without fathers. They may have had a seemingly fulfilling life but only we could see the vacuum in their hearts and the thirst and longing in their eyes. We may heal with time if a loved one dies under natural circumstances but a void remains in the heart if they are brutally snatched from us for no sensible reason.

Sajid, I wish your family finds the strength to bear your loss. I wish your children grow up as complete persons without any longing and void in their hearts. A heavy responsibility has fallen on your wife’s shoulders. I hope she learns to live with it and comes out as strong as ever. I wish your parents healing. I wish your siblings and friends carry on your legacy as you were one of our national assets, and I wish wherever you are, you find peace and freedom.

Farewell Sajid! Rest in power!

Maryam Khanzai is a humanist. She often campaigns for the rights of the Baloch people, especially the missing persons. Her interests include politics, literature and feminism.