What’s happening in Balochistan is beyond sad. But we have to swallow this bitter truth. Numerous people have been whisked away, tortured in dungeons for years and thousands of decomposed bodies have been found in desolate places and, in some cases, tossed into mass graves. This killing of an unknown number of Baloch people has caused the vanishing of countless dreams of not only individuals but society at large in Balochistan.

The present Baloch situation in Pakistan can be compared with the genocide of the Bengalis in the 1970s. They were brutally killed and systematically marginalised by Pakistani state institutions for years, until December 16, 1971, when they succeeded in gaining independence and formed a new country, Bangladesh. Like the Bengalis of the time, the people of Balochistan are living under the State’s military regime. Although other minorities such as the Pashtuns and the Sandhis also suffer abuse in Pakistan, it is the Baloch who have a longer history of a political movement to express their anger, hurt and protest.

We attempt to seek justice through the legal structure of Pakistani law, which often leads us nowhere. The real masters under the guise of this cosmetic democracy reside in the army headquarters in Rawalpindi. It is they who run Balochistan with no inclination toward justice for the disenfranchised Baloch people.

Despite living under the shadow of this ruthless military rule — with our hearts full of fear and grief in a war-ravaged land, where every family has suffered the loss of a member either through conflict or at the hands of the army — we still live the best we can. We send our children to school with hopes of a better future, hopes of living in a land where our existence is respected, where our future generations can live with dignity, liberty and peace. However, this dream of peace, prosperity and being treated with respect as citizens is yet a far-off one. The looting of Balochistan’s resources, the chain of unending wars and the enforced disappearances are illustrations of the large-scale oppression of the Baloch people.

However, as a human rights activist, I cannot ignore the systematic violence and selective annihilation of my nation. It brings devastation, grief, and hatred to families that neither the government nor the army seems to care about. It is this specific physical and psychological undermining of individual human life, of friends, family members, the young and the old alike, that strikes the heart, one that we have hoped will lead to the world listening to us and our cries for a decent life in our homeland. For that, really, is all we are asking for.

Such violations, the complete disregard for human life from the authorities and the constant fear of being watched, are the most reprehensible. Let me share an anecdote here. On a lovely sunny day in mid-September, 2012, I and two other friends got off a local bus in Malleer, Karachi. As my friend Raza Jahangir, a student activist, put his feet on the ground, he took a deep breath and looked behind to check if we were being followed. “I wish I didn’t have to worry that anybody was following me, so I could just live my life as a student and continue to protest for our rights as a Baloch without fear, like a normal human being,” Raza said. When he made this comment, we guessed he was thinking of his friend Qambar Chakar, whose decomposed body had been found dumped eight months earlier. “You never know when the State will send its troops or sponsored killers to not only kill you but also disgrace your body. Only to make the people like you think that when you resist, this is what your end will look like,” he said. At the time, we ignored him because we didn’t like to dwell on how insecure and under surveillance our lives were even within the allowed limitations. Raza was more prescient than we realised.

About a year later, he was shot dead by the Pakistani paramilitary troops in Aapsar, Turbat, along with another human rights activist. Raza’s only mistake was that he was a student activist. The forces of a nuclear state felt threatened by, and had to kill, two unarmed young men, who believed in democracy and human rights. Scores of like-minded students and young people have suffered a similar fate over the years. Some were killed, some were abducted and are still missing and some were coerced into quitting activism.

This all was done to alienate my generation from Balochistan’s real problems. However, instead of eliminating dissent, the actions of the Pakistani army caused the opposite to happen. Many activists involved in the long-standing political movement went underground to continue fighting for their rights, believing their activity was now more important than ever.

In 2017, the intelligence agencies changed their tactics against those Baloch activists who had gone underground by instituting “collective punishment”. Instead of just going after the activists themselves, the State started abducting family members as well, striking a deeper fear for their loved ones into them.

As time passed, abductions continued and the tactics of dealing with the Baloch got more aggressive. The State deployed thousands of more paramilitary troops over the entire Balochistan region, increasing military installations, check-points and patrolling. Such actions humiliate ordinary people who are just trying to live their everyday lives; lives which are worsened by the now existence of numerous torture cells, sponsored local drug mafias and death squads in Balochistan.

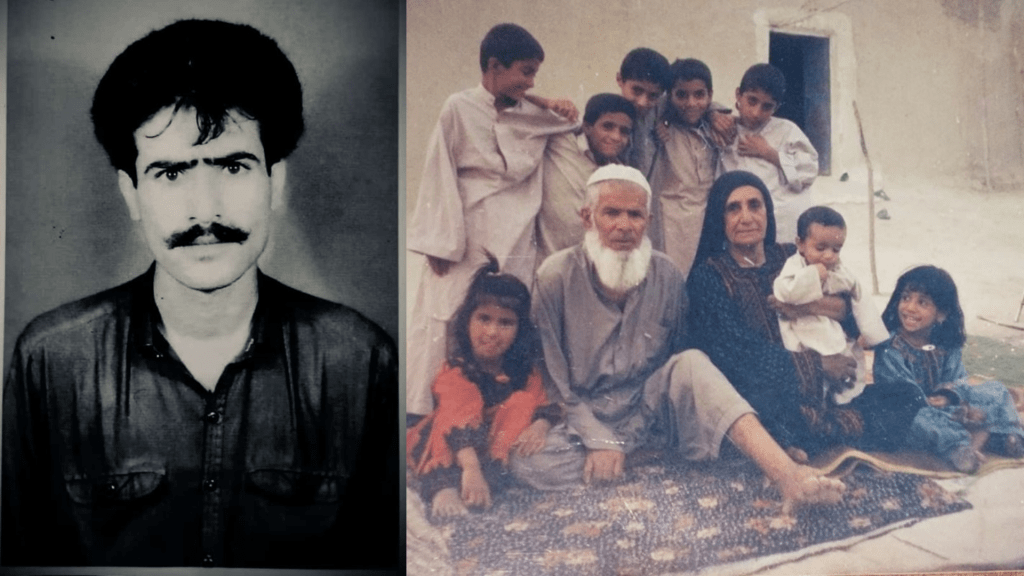

The nature of this aggression was further exemplified by the murder of Hayat Baloch. The 27-year-old student was the first member of his poor, hardworking family to attend the University of Karachi, where he was completing his degree in Physiology. He was peacefully pursuing his degree – with no involvement in politics – with hopes for the future of being a civil servant and helping his family. On the eve of Pakistan’s Independence Day, August 13 of this year, a routine paramilitary patrol was attacked by an improvised explosive device, planted by unknown assailants in Aapsar, Turbat. Soon after the attack, the troops started searching for the unknown militants. In a nearby orchard, they found Hayat working with his aged parents. They grabbed him in front of his parents, blindfolded him, bound his feet, and dragged him off, although still within the sight of his mother and father. They then shot him eight times, despite his parents pleading to the soldiers repeatedly that their son had been working with them since the morning and had not left for a minute.

Under the State’s seeming well-organised systematic oppression, the army did not plan on Hayat’s murder going viral. But it did beyond what they had experienced with their previous covert murders of Baloch people. The tragic murder of the innocent young man was carried out in clear daylight in front of witnesses. A photo of Hayat, his bullet-ridden body lying on the ground with his grief-stricken parents by his side, went viral, trending on Twitter with the hashtag #JusticeForHayat. Because of this, Hayat’s family was able to file an FIR, forcing the army to own up to the murder. Attempting to exonerate themselves with an excuse, the Frontier Corps, a paramilitary force stationed in Balochistan, said that one of their soldiers had panicked after the IED attack and killed Hayat, shooting him eight times.

Had Hayat’s murder not occurred close to a populated area and in broad daylight, it was almost guaranteed that the State would have put his name on a traitor’s list, telling the world that they bravely killed a traitor in a militant battle, besmirching his name forever.

After the murder of Hayat Baloch, the FC handed over the guilty soldier to the police. It has been three months, but there is no sign of justice. Although it can only be hoped that he is still in police custody, it is highly unlikely that justice will be served as the army does not punish its own for the loss of Baloch blood.

But in Pakistan, it doesn’t matter if they are clandestine murders of activists or “accidental” murders of the innocent, the end result is still the same for all of us: Freedom of expression, human rights of any kind, “life, liberty, and happiness”, will get us killed – or worse. The oppression of Baloch people, Pakistani citizens, continues with no end in sight.

As a young student activist, I was also an idealist. I heard that there is an international human rights mechanism in the West and thought that they surely would come to our aid. What I didn’t understand is the murder of individuals, the attacks on the family, the culture of fear that Baloch are forced to live under isn’t the cruelty that catches the world’s attention. Neither Western liberal politics nor its international humanist human rights mechanism speaks up against this systematic brutality.

Only a few voices from within Pakistan condemn this abuse of power by the secret agencies. Sometimes, some so-called Pakistani democratic parties shed crocodile tears on the atrocities in Balochistan, only using our plight as a political card. The same parties when in power do not take concrete action; they do not go beyond meaningless words and empty promises, just point-scoring, nothing more than that.

However, despite this slow dismantling of Baloch society, there still exists a complicated hope for a coalition of like-minded individuals who believe in freedom and democracy to come to the aid of Balochistan, championing their fight against the Pakistani military regime. Meanwhile, the fight against this oppression will continue, in the actions of individuals who believe silence is not an option and in the struggle of those individuals who are scattered across the globe writing and offering whatever support they can for those who cannot speak up for themselves. It is my hope that one day more people will come to the aid of those who live in this dire situation in Balochistan. Perhaps even you.

Noroz Hayat is a writer and a human rights activist based in the United States. He writes in Balochi and English on human rights situation of Balochistan. He is affiliated with Human Rights Council of Balochistan.