What a time to be alive. As a global pandemic, an economic crash and despair are sweeping the world, so too are anti-racists movements inspired by the reawakening of Black Lives Matter following the brutal murder of George Floyd by US law enforcement. At such a time, I can’t help but be compelled to think about the racial injustices in my communities.

I am a British-born Baloch woman of mixed Black and Iranian ancestry. I now take undiluted pride in my heritage, and in the racial diversity of the Baloch. But this was not always the case. The bitter reality is that our Black brothers and sisters and those with darker skin or mixed racial heritage face prejudice and mistreatment within our community, leading a significant number of the Baloch to live in denial and secrecy about their Black heritage. With a renewed commitment to combatting racism around the world, it is time to confront racism and colourism among the Baloch as well.

When discussing racism, I have to draw on my personal experiences and the prejudice I have felt, not just as a member of an ethnic minority in millennial England but as a Baloch of mixed racial heritage. To even begin to explain a fraction of my own identity, I will begin with my Great Great Grandma (paternal), whose name we believe to be Nazatoon. Little is known about her besides the fact that she was a Black woman. Nazatoon married a man of Iranian heritage and gave birth to a baby girl called Mahbibi. Mahbibi is said to have been beautiful, with some of her mother’s African features but her father’s fair skin. Nazatoon asked her sister Zalia to take Mahbibi to Karachi for marriage, and at an unknown age, she married my Great Grandad Umar Baksh (also my Great Great Uncle on my Mother’s side) who was of Black heritage. Sadly, after arriving in Karachi Mahbibi never saw her mother again.

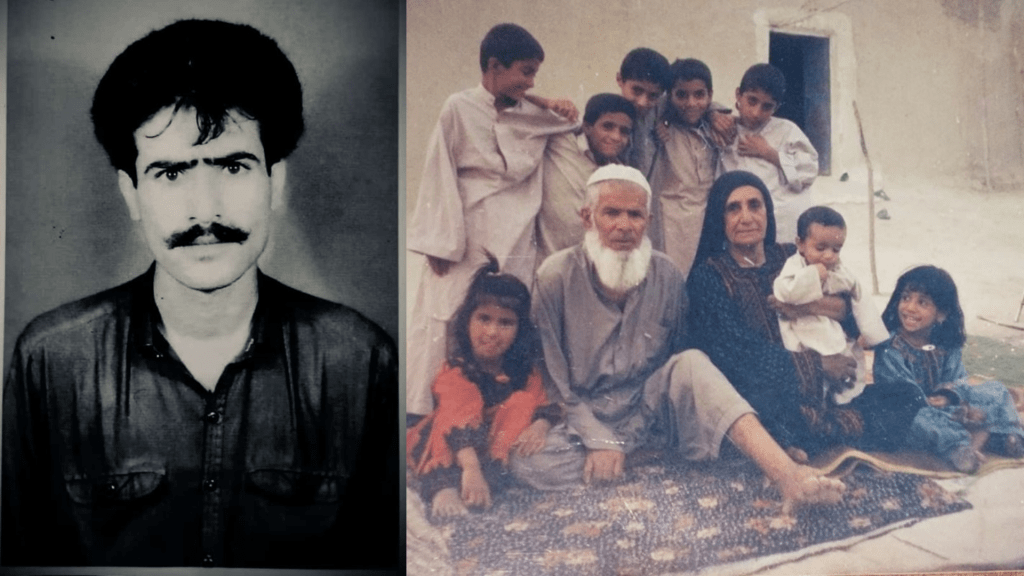

Fast forward to the 1940s. Mahbibi’s son Rasool Baksh (my grandfather, more affectionately known to me as Babu) fell in love with my Grandma Sharipah. Shairpah was a fair-skinned woman of ‘pure’ Baloch descent. Their families were outraged; at that time inter-tribal marriage was very rare, let alone inter-racial marriage. My grandma’s mother was particularly strongly against the union as she saw Babu as a Black man of mixed blood.

My grandparents defied their families, married, and had five children. They then moved to Bahrain in search of a better life. My grandparent’s marriage was tumultuous. After a short-lived romance with Sharipah, Babu sent his family back to Lyari and carried on a pursuit of pleasure and passion alone, first in Bahrain and then in England. Only after 10 long years and constant pleas from his estranged wife, did Babu finally agree to bring his family to England, by car. After four weeks on the road, they finally arrived in Hull, England, on October 3, 1971.

Sadly in 1997 my grandad passed from bowel cancer. I was only three years old, and my memories of him are few and far between. A lot of the stories I have been told are from my mother, grandma and father. They describe him as artistic, open-minded and free-spirited. My mother told me, however, that he never accepted his Blackness, but confidently glorified his Iranian heritage. When he spoke about his mother Mahbibi he would hide the fact she was mixed race and fixated on her ‘white-ness’. He was reluctant to speak about his Grandma Nazatoon at all, and his Father Umar Baksh’s mixed racial background didn’t matter as “he was from a wealthy family.”

As my mother and others in my family recall, my grandfather’s denial did not stop my grandma Sharipah often directing racial slurs towards him during arguments, referring to him as “Mazan Granz” (“wide nose”) or “Nare Sheedi” (Sheedi is one of the many derogatory Balochi words for Black people), and even “Teeh”, which is highly offensive too. The most brutal word of them all for me is “Raghi” which loosely translates to “Black/Bad Blood”, a word that tormented me throughout my childhood.

The racial denial displayed by my grandad was often mirrored by my father and his siblings. When my father arrived in England in 1971 racism at the time was pretty much black and white (pun intended!) It was strictly “NO IRISH. NO BLACKS. NO DOGS”. This was especially true in the North of England. My father is darker-skinned than most of his siblings and he has also inherited more of his father’s “African” features. He had soft curls in his hair that could be combed straight, very much like his mother’s and mine. My father’s siblings, by contrast, could be described as ‘racially ambiguous’. This means that they can easily pass as Pakistani/Iranian.

My upbringing in England was fraught with contradictions. After they moved to England, my dad especially preferred to identify as Pakistani Baloch but heavily identified as Pakistani. It wasn’t until I was in my teens that my dad started to speak more openly and passionately about being Baloch and to encourage us to identify as just Baloch. At the time I was angry and thought it was too late for all this because I already had friends from all walks of life, I had already begun identifying as Pakistani, and I had already experienced racism from the Baloch, Pakistanis, and Iranians alike. Another contradiction was that my father taught us to be anti-racist, but made it clear he would never be happy if we married Pakistanis. And I was still expected to tick the “British Pakistani” box on all surveys.

In high school, I was always trying to just blend in and be accepted by the Pakistani kids, partly because I knew how all the South Asian and Middle Eastern kids in the school talked about and treated Black people. However, one day when I was walking to my history lesson, a Pakistani boy in my year group stopped me and asked: “Sammi, you’re a P*ki right?” I responded, proudly, “Yes, I am.” He began to laugh at me.“You’re such a liar,” he taunted, “You’re not a P*ki. You can’t even speak Urdu and I’ve seen your dad pick you up from school. He looks Black. Your uncle who picks up your cousins looks like a F****** N****!!”

I remember feeling like I had just been outed for a secret I didn’t even know about properly myself. To me, my dad just looked Baloch, to me he was just my dad. My parents had not prepared me for anything like this.

These kinds of incidents happened throughout my life; if some Pakistanis told me I was “too dark” to be one of them, others told me I was “too light” to be a Baloch. When I was around 21 years old, my mother and I were at Karachi International Airport waiting for our baggage, when a security guard came over and spoke to me in Urdu. My mum very kindly explained that I didn’t speak Urdu, only English and Balochi. The man looked at us with disgust and hatred, and asked my mother why she didn’t teach me Urdu and if I was really Baloch why wasn’t I darker-skinned with kinky hair like the Baloch he had seen.

However, I must admit, the backhanded and racist Shegans (taunts) had begun at home for me, and within my own family. Every other summer as children, we travelled to my parents’ respective homes in Karachi, Pakistan, my dad hailing from the ghettos of Lyari and my mother from poverty-ridden Malir. Both of these areas are predominantly Baloch, mostly Black and severely deprived. In the summer of 2004, I was sitting with my cousins when someone pointed out that I was only slightly lighter compared to one of the others, but my hair was nicer. It was a good thing, she remarked, that my hair was not still curly like in my baby photos. Then I would have looked more ‘Raghi’, like my cousin, who looked ‘Somali’. No one knew that I was endlessly combing out my curls and blow-drying my hair so it could stay straight; in fact, when I got older I would have semi-permanent hair extension installed so I could hide my curls. They began to taunt my ‘Somali’-looking cousin and call her names. In hindsight, I wish I had said something then, but we were children and surely children shouldn’t be doing the work of adults.

Taunts like this were common and they were used all the time in my family. It was just racism hidden in the form of jokes. But these jokes destroy people and their self-esteem. The cousin I speak of later went on to buy risky bleaching creams in an attempt to look lighter. Even on a visit to Karachi in 2019 my Aunty (paternal) who is the same complexion as I am, but with ‘Arabic’ features, was upset with me when I rejected her offer to have skin lightening treatment done.

With my family in England there wasn’t much difference. My paternal cousin is almost identical in appearance to me, except for my slightly darker skin and wider nostrils. The best way to describe her is ‘The Poster Girl for Baloch Beauty” with very Middle Eastern/Arabic features: whiter skin, thin lips and a thin nose. Her mother had Pashtun heritage so naturally she was extremely fair-skinned. Now as adults, a topic we often come back to is how much people would compare our looks when we were growing up. She was always being told she was very beautiful. Myself, on the other hand, I can’t remember a time where any of my uncles or aunties ever called me beautiful. “You’re light enough not to complain but dark enough not to marry.” These words were said to me in passing once and they stuck to me like glue at the time.

If I had been given more information about my Black heritage as a child, it would have given me more confidence in facing up to this bullying and prejudice, both within and outside the family. But my family’s silence and even denial left me unprepared. This proved detrimental to my development as a child and has left lifelong negative effects on my mental health and my identity as a Baloch.

Now when I mention my Black heritage it is automatically assumed that all my ancestors were slaves. But not all Black Baloch were slaves, nor all Baloch slaves Black. When researching slavery in the Middle East and the Arabic slave trade, I learned that native Baloch as well as Black people from East Africa were enslaved by Iranians, especially along the South Coast and Gwadar where my family is originally from. And not all dark-skinned Baloch were slaves. My Great Great Grandfather Wajah Sabroh (Father of Umar Baksh) was indeed a dark-skinned man with mixed racial heritage from Passini, Balochistan, but he came to Karachi for business and purchased lots of land across the city. He was a wealthy landowner.

My Great Great Grandfather’s story is, however, exceptional. It’s no secret that the situation of the Black Baloch has not improved much throughout time. It is nearly impossible for Black Baloch to obtain an Iranian ID card (Kart-e-Melli), and with Pakistan only abolishing slavery as late as 1992, there are still hidden acts of slavery taking place today, especially against Black/darker skinned Baloch both in Pakistan and Iran.

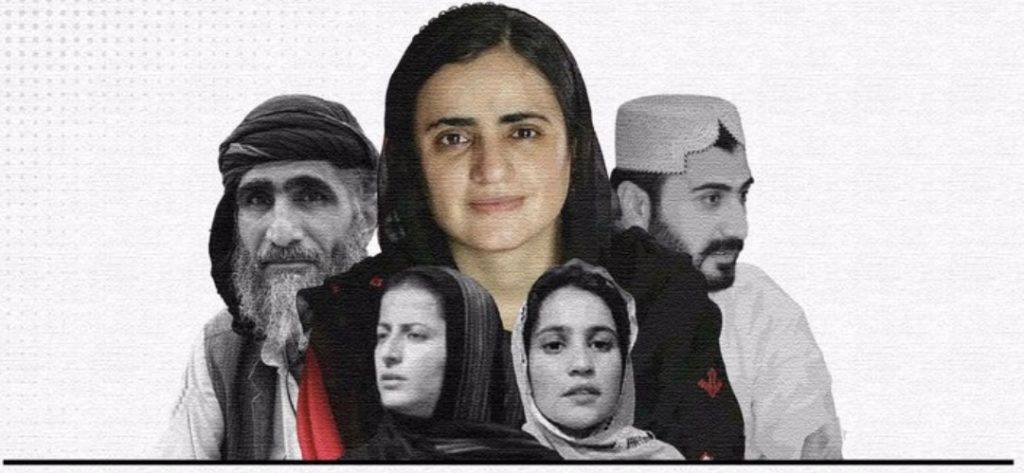

I have been speaking out of my own experiences of racism as a woman of mixed heritage. I know I cannot fully understand what my brothers and sisters of darker complexion must have experienced in the Baloch community and across the globe. What I do know is that for the first time in my life I feel very proud of all aspects of my heritage. I urge all the Baloch who are Black or have any Black ancestry to stand tall and be proud of their wide noses, kinky or curly hair and curvaceous bodies and to love their beautiful black skin, whatever the shade.

Sammi Baloch is a poetess, artist and mental health advocate who has been featured on the BBC. She is “a very proud Baloch” living in North West London. She also owns Doochi, an online outlet that sells handmade Balochi attire.