After attending an event in Bonn about Balochistan in April 2022, we stopped at Lützerath on our way back. Lützerath was a resistance camp—one of the first efforts to block the RWE coal mine, which had become a focal point for Germany’s rising climate change resistance movement. The entrance roads were blocked with cardboard, branches, and stones. Treehouses were built to slow down the inevitable evacuation. Workshops were held daily, and strategies were crafted to counter police invasions. It wasn’t just a protest against a coal mining company anymore; it had evolved into a global resistance hub. The court had already ruled in favor of the mining company, and it was only a matter of time before the police would evacuate the place. The activists were determined to fight—one last attempt to save the villages that were doomed to be destroyed.

For me, it was an escape from my own traumatized mind, entangled in German bureaucracy, my asylum case, the atrocities in Balochistan, and the exile that feels like a chronic disease for those of us who can never return home. Lützerath felt soothing, like my village. Firewood crackled in the air, and the smell of food cooking brought a sense of comfort. People were sharing spaces, connecting with each other, and finding solace in this community.

My interest was a selfish one; I saw it as a good place to retreat for a weekend. After waiting over six years for my asylum application, I was unable to think beyond my immediate need for peace.

Not long after, there was a protest in Lützerath. It was there that I first met Sulti.

Sulti was a young, energetic activist from Kurdistan who had walked all the way from Kurdistan to Germany in 2015. Like most immigrants, Sulti was struggling with the asylum process, but for them, it wasn’t just the process—it was the entire system. While I was there to escape the system for a weekend, Sulti was there to fight it.

I think Sulti soon realized that this very system was affecting people both here and back home. They wanted to build a resistance movement with migrant activists, striving to bring everyone together for a collective resistance.

A year later in June, we met again at an anti-deportation camp in Berlin. By then, my asylum case had been accepted, but Sulti was still fighting the system—for the people, with the people. This time, they had managed to bring together several migrant activists, forming bonds forged from collective pain and suffering. Sulti served as the connection point for activists from different backgrounds. For most of us, the common thread was Sulti. During a pause for dinner, I heard a distant chant of the slogan “No Border, No Nation, Stop Deportation.” It was Sulti, coming towards us with a speaker and a mic, inviting everyone to share their experiences. There was no break for Sulti.

Amazingly, it worked. People began stepping up to the mic and sharing their painful and traumatic experiences. Listening to these stories, I realized that it wasn’t just me—everyone who took the mic had a horrible story to tell. This time, it hit differently. I felt we were all trapped in a system where each of us believed our experience was the worst. But for Sulti, it was clear that the system itself is the problem, and that we had to break free from this trap of individualism

We sat and talked. I knew Sulti had probably discussed forming a Global South resistance with hundreds of people, and I was just another addition. But their enthusiasm and dedication left an impact.

Months passed, and we met several times. In one of our meetings, I asked them what the turning point in their life was. They replied, “The journey from Kurdistan to Germany.”

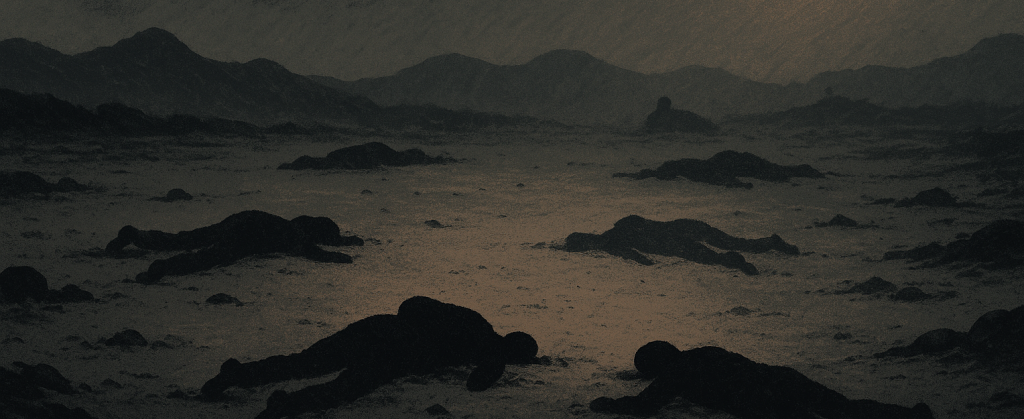

Sulti had been separated from their parents in the Mediterranean Sea at the tender age of 17. The parents didn’t know if their child was alive, and Sulti didn’t know if their parents had survived the journey. Along with Sulti, another child had also been separated from their parents. Sulti was left on their own, with a chronic disease, in a place where they knew no one, and with a child they couldn’t abandon. “I became a mother, a father, and a provider overnight,” Sulti said.

It took three years for Sulti to find their parents in Germany. “I was a different person, I was not the same child who was left behind.”

The last time we met was in Freiburg in November 2023, where Sulti was part of a panel discussion against European borders. Their co-panelist, a white person, grew defensive and racist in response to Sulti’s arguments. He said, “You (BIPOC) are weird to us, and we (white people) are weird to you. We don’t necessarily need to be in a love relationship.” Sulti calmly replied, “Before demolishing the borders between countries, we should begin with demolishing the borders in our minds.”

On August 19th, Sulti passed away after fighting their illness for 10 days. The doctors put them in an artificial coma from which Sulti never woke up.

Sulti’s spirit of organization and resistance was reflected in their remembrance. There were activists from diverse backgrounds. We mourned Sulti collectively. It was both painful and empowering at the same time.

I am sure that whoever met Sulti felt their impact. Sulti created spaces where pain could be transformed into collective action.

The juxtaposition of our personal struggles with the broader fight against climate change and systemic injustice reveals how these global issues resonate deeply with those who have experienced displacement and trauma.

Sulti’s life, marked by resilience and unwavering dedication, is a poignant reminder of the human cost of migration and the lengths to which individuals go to seek safety and justice.

It also serves as a reminder that while individual lives may be fleeting, the impact of one person’s courage and dedication can resonate far beyond their time on earth.

Sulti lived short but big.

As the revered Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote:

How can I convey to you, my friend

how horrible is a night of lonliness *

It would suffice to me

if there were just some count

I would gladly welcome death

if it were to come but once.

My dear Sulti, the Human of Colors—rest in peace, finally.

Abdulla Abbas is executive director of Human Rights Council of Balochistan. He lives in exile in Germany and can be reached at @AbdullahAbbas